The intense demand for skin care and Vitamin A

Anti-aging Skincare Market

The intense demand for skincare is rising due to people’s growing awareness of appearance. The skincare market, promising and full of potential, is definitely worth investigation and scientific work.

Among them, anti-aging skincare products hold a noticeably significant proportion, which sheds light on the importance of combating aging problems.

Sensitive Skin

Skin sensitivity is widely observed in China. People with sensitive skin become more vulnerable because of wearing masks and unbalanced lifestyles during Covid-19. People are thus in urgent need of effective and mild skincare products.

Potent Vitamin A in Skincare Products

The prototype of retinoids, retinoid acid, was an acne killer initially. Retinoic acid was found to reduce wrinkles and reverse aging with further study and clinical use. It was finally approved by FDA as the only optical molecule to treat photoaging.

Vitamin A Chemical Manufacturing

Currently, the industrial manufacture of Vitamin A is based on chemical synthesis that is well-developed and productive.

However, chemical synthesis has inevitable shortages, such as unsustainability, high carbon emissions, and high pollution since the raw materials are derived from petroleum.

Customer’s Demand And Needs

For customers using Vitamin A, the slightest irritation and reasonable prices are in demand for retinoid products with considerable sustainability.

Biosynthesis of Vitamin A

Our Object

Considering all ineffaceable shortages of chemical synthesis, we’re determined to develop a retinoid biosynthesis pathway to realize another sound synthesis of Vitamin A.

Additionally, we are concerned about the environmental pollution brought about by chemical ways and constructing an environmentally-friendly biological synthesis with fewer by-products and lower costs.

To accomplish our goals, our bioreaction highlights the production of retinoids and their precursors. We need to find the necessary chemical groups and insert them into bacteria through enzymes.

Four problems need to be concerned about

Flux imbalance: the imbalance between substrates and enzymes

Loss of intermediates: lack of specific enzymes and loss in yield

Pathway competition: competitions from the natural physiological process of bacteria and product reduction

Toxic intermediates: interfering with the natural growth process of cells, thus preventing the production of cellular physiologically essential chemicals and consequently leading to cell damage or death

Our trials and difficulties

At first, we aimed to produce an esterified retinoid: HPR. Sadly, since one of the substrates for HPR is biologically toxic, we had to quit this idea and turn to retinyl retinoate. But still, this target product had two weaknesses: one unavoidable intermediate (retinoic acid), which is hard to remove from our final products, is banned in skincare products; and retinyl retinoate lacks clinical evidence for its effectiveness. Further, we tried to synthesize retinyl palmitate, the most studied esterified retinoid. However, its unsatisfactory efficacy and poor transdermal delivery forced us to give up. So we failed to get any optimistic feedback from esterified retinoids.

New ideas:

We came up with our final thought inspired by the 2016 Glasgow. Based on their composite part, crtEBIY, we complemented an oxygenase BCMO and a reductase ybbO to synthesize retinol, our ideal final product. However, there still existed some issues with our design. Extraction of retinol and other remaining retinoids required further thinking. More, the final product’s purity and biosafety needed consideration.

Our project

Rester: A Sustainable Single-Cell Factory for skincare Vitamin A production

Initially, we attempted to synthesize esterified retinoids but in vain. Then we proposed a single-cell factory capable of producing retinol sustainably. After proper extraction, our retinol can be used for either cosmetic or other chemical uses.

Future improvements

Recomposed formula: 1+1>2

Though we can only harvest retinol-like retinoids through our single-cell factory, in our following experiments, we’ll try to make compounds with retinol and other antioxidative ingredients like glycine soja oil or Vitamin E to provide comprehensive skincare functions.

Back-end production: microsphere and other wrapping technology

Microsphere or liposome wrapping has been proven one of the most effective and widely used cosmetic delivery systems, by which they can be utilized to a greater extent.

CRBP design: To protect our environment

As a classic lipid, retinoids are hydrophobic. Still, we can change the characteristic by combining cellular retinol-binding protein (CRBP) with retinol, thus turning it into a molecule able to be transported in liquid. This way, we can improve the retinol use ratio and alleviate possible environmental contamination.

Better esterifying solutions

Despite our disapproval of esterified retinoids listed above, these compounds still possess great value only if we can figure out a better-esterified form. We may sort different candidates through chemical methods and try some potential possibilities.

Description of single-cell factory

We developed a single-cell factory for efficient production of β-carotene, retinaldehyde and retinol. This single-cell factory contains the following two modules.

- Four coding sequences required for the carotenoid biosynthesis pathway were separated by self-cleaving ribozyme to construct a ribozyme-assisted polycistronic co-expression BioBrick in E. coli.

- Retinal dehydrogenase expressed by gene ybbO is enriched by TEARS, which are assembled by RNA-binding protein recruitment domains fused to poly-CAG repeats that drive liquid-liquid phase separation from bulk cytoplasm spontaneously.

Here is described the rationale behind the design of our single-cell factory as well as an overview of our experimental design.

Module: Ribozyme-assisted polycistronic co-expression system for carotenoid biosynthesis

Enzymes required for the synthesis of β-carotene

β-carotene is an organic, strongly colored red orange pigment abundant in fungi, plants, and fruits. It is a member of the carotenes, which are terpenoids (isoprenoids), synthesized biochemically from eight isoprene units and thus having 40 carbons. As the most common form of carotene in plants, β-carotene is distinguished by having β-rings at both ends of the molecule. The most important function of β-carotene in higher plants is to protect organisms against photooxidative damage. In mammals, β-carotene functions as a precursor of Vitamin A.

Studies have shown that crtE, B, I and Y, four enzymes taken from the Pantoea ananatis genome, are a part of the carotenoid biosynthesis pathway (Misawa, N et al. 1990). Geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase (crtE, BBa_K118014) converts farnesyl diphosphate to geranylgeranyl diphosphate. Phytoene synthase(crtB, BBa_K118002) converts geranylgeranyl diphosphate to phytoene. Phytoene dehydrogenase(crtI, BBa_K118003) converts phytoene to lycopene. At the end of the reaction chain, lycopene β-cyclase (crtY, BBa_K118008) converts lycopene to β-carotene. Since E. coli can synthesize farnesyl diphosphate on its own, our focus on the carotenoid synthesis enzyme family will be on the above four enzymes.

Figure 1. Reaction pathway of carotenoid biosynthesis.

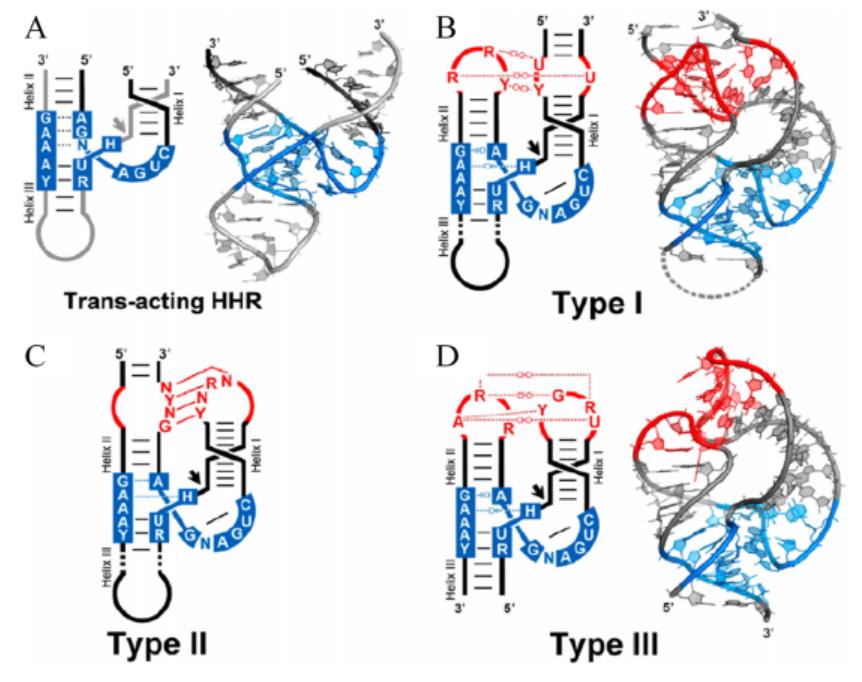

Hammerhead ribozyme, a candidate of self-cleaving ribozyme

Ribozymes are non-coding RNAs that promote chemical transformations with rate enhancements approaching those of protein enzymes. Of the 11 previously validated ribozyme classes, 6 are self-cleaving ribozymes, and hammerhead ribozyme is one of them (Weinberg, Zasha et al. 2015). Hammerhead ribozyme was first found in the genome of viruses and viroids. It is involved in the processing of RNA transcripts based on rolling-circle replication. The tandem copy of the RNA sequence will be generated in the roll ring replication, and the self-cleaving activity of ribozyme can ensure the generation of RNA copy of unit length.

The secondary structure of hammerhead ribozyme resembles a hammer. According to different open helix tips, hammerhead ribozymes can be divided into three types: TypeⅠ, Type II and Type III. The catalytic center of ribozyme consists of 15 highly conserved bases surrounded by three helixes (HelixⅠ, Helix II and Helix III). The long-range interaction between HelixⅠ and Helix II can help stabilize the conformation of the catalytic center of the enzyme and improve the catalytic efficiency (Jimenez, Randi M et al. 2015). While working, ribozymes utilize a network of defined hydrogen bonds, ionic and hydrophobic interactions to generate catalytic pockets, which capitalize on steric constraints to generate in-line cleavage alignments and general acid-base chemistry to catalyze site-specific cleavage of the phosphodiester backbone (Ren, Aiming et al. 2017).

Figure 2. Overall tertiary structure of different types of hammerhead ribozymes. Blue marks highly conserved bases. The black arrow marks the digestion site. Red marks the long-range interaction between HelixⅠand Helix II (Jimenez, Randi M et al. 2015).

Inserting ribozyme sequences between crtEBIY

Before 2022 Team Fudan, a number of teams made efforts to build an efficient BioBrick which converts colorless farnesyl pyrophosphate to orange β-carotene using coding sequences of crtEBIY. 2016 Glasgow created BioBrick BBa_K2151200 through standard BioBrick assembly of BBa_K118014 (RBS+crtE), BBa_K118006 (RBS+crtB), BBa_K118005 (RBS+crtI) and BBa_K118013 (crtY). They assembled crtEBIY close together in sequence, put them under the same promotor and experimentally explored the optimal assembly order. However, as many researches indicate, the major problem of polycistronic vectors, which contain two or more target genes under one promoter, is the much lower expression of the downstream genes compared with that of the first gene next to the promoter (Kim, Kyung-Jin et al. 2004). The tail of the coding sequence can interfere with the head of the ribosome binding site (RBS), which can hinder RBS from combining with ribosomes. Therefore, we hope to find alternative ways to further improve the efficiency of the crt BioBrick.

Instead of assembling CDSs sequentially, we construct a ribozyme-assisted polycistronic co-expression BioBrick (pRAP) by inserting ribozyme sequences between crtEBIY. In pRAP, the RNA sequences of hammerhead ribozyme conduct self-cleaving, and the polycistronic mRNA transcript is thus co-transcriptionally converted into individual mono-cistrons in vivo. Self-interaction of the polycistron can be avoid and each cistron can initiate translation with comparable efficiency. Besides, we can precisely manage this co-expression system by adjusting the RBS strength of individual mono-cistrons. The following is a conceptual diagram that vividly depicts the above process.

Figure 3. Transcription, self-cleaving and translation processes of crt genes. This process also mimics to some extent the processing of precursor mRNAs in the nucleus in eukaryotic cells.

Module: Spatial engineering of E. coli with addressable phase-separated RNAs (TEARS)

Using pRAP in E. coli by inserting ribozyme sequences between crtEBIY, we get β-carotene. In order to synthesize retinaldehyde and retinol, we introduce the protein BCMO (BBa_K4162004) and gene ybbO (BBa_K4162003) to our single-cell factory, coding for β-carotene mono(di)oxygenase and aldehyde reductase respectively (Jang, Hui-Jeong et al. 2015). β-carotene can be cut in the middle by BCMO to form two molecules of retinaldehyde and aldehyde reductase incompletely converts retinaldehyde to retinol with the assistance of NADPH.

Figure 4. β-carotene can be cut in the middle by BCMO to form two molecules of retinaldehyde

Since retinol is regarded as a superior raw material for skin care products, we tried to improve the production of retinol and its proportion in the product by enriching the aldehyde reductase expressed by gene ybbO (Jang, Hui-Jeong et al. 2015).

Memberless organelles formed in prokaryotes

Living systems coordinate complex biochemical reactions using intracellular spatial organization, a powerful strategy that bioengineers have long sought to replicate (Martin, William 2010). In eukaryotes, membrane-bound organelles creat an isolated environment that can be reprogrammed by fusing components of interest to organelle-targeting domains (Hammer, Sarah K, et al. 2017). However, prokaryotes generally lack universal organelles, posing an attractive challenge to engineering synthetic alternatives. To this end, modular DNA-, RNA- and protein-based scaffolding, widely found in natural systems were engineered or rationally designed for various metabolic engineering applications and control of gene expression (Tsai, Miao-Chih et al. 2010). Engineering such scaffolds is hindered by difficulties to cluster large numbers of different enzymes or delocalizing enzymes to prevent unwanted crosstalk.

Membraneless organelles are formed through a common liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) process that condenses a variety of biopolymers (Bracha, Dan et al. 2019). Biopolymer condensates can be derived from a single component and may adopt flexible sizes or shapes, facilitating rational design. In comparison, membrane-bound organelles require complex processes of biogenesis and regulation, and protein-shelled microcompartments have a precise multicomponent assembly of fixed shapes and sizes.

A transcriptional fusion of an LLPS domain to an aptamer-based protein

TEARS features a transcriptional fusion of an LLPS domain to an aptamer-based protein recruitment domain, forming an intracellular separated RNA solvent, to which additional components (solutes) may be scaffolded to introduce customized functionalities. Phase separation is achieved using CAG triple-ribonucleotide (rCAG) repeats. TEARS are shown to exhibit programmable selective permeability, acting as solvents only for specific aptamer-targeted components. The ability of TEARS to exclude bulk cytoplasm may explain their limited toxicity and minimal effects on cellular growth (Guo, Haotian et al. 2020, 2022).

Figure 5. The combination mode of recruitment domains and binding domains.

Construction of fusion protein of aldehyde reductase expressed by gene ybbO tagged with tdMCP-GFP

We use tears in our design to enrich aldehyde reductase by constructing a plasmid inserted with gene ybbO tagged with tandem-dimeric MS2 coat protein (tdMCP-GFP). Attached to aldehyde reductase expressed by gene ybbO with the help of a piece of linker, coat protein is able to bind to the MS2 aptamer. GFP, the tag protein, helps display fluorescent imaging of cells with diffuse tears droplets inside (Figure 5).

It is important to mention that BCMO as a membrane protein can be disrupted in its conformation and therefore unable to function if it is enriched in the cytoplasm. Therefore, we did not choose to use TEARS for BCMO enrichment. Our modeling supports our design.

Figure 6. TEARS for retinol production.

References

Misawa, N., Nakagawa, M., Kobayashi, K., Yamano, S., Izawa, Y., Nakamura, K., & Harashima, K. (1990). Elucidation of the Erwinia uredovora carotenoid biosynthetic pathway by functional analysis of gene products expressed in Escherichia coli. Journal of bacteriology, 172(12), 6704–6712.

Weinberg, Z., Kim, P. B., Chen, T. H., Li, S., Harris, K. A., Lünse, C. E., & Breaker, R. R. (2015). New classes of self-cleaving ribozymes revealed by comparative genomics analysis. Nature chemical biology, 11(8), 606–610.

Jimenez, R. M., Polanco, J. A., & Lupták, A. (2015). Chemistry and Biology of Self-Cleaving Ribozymes. Trends in biochemical sciences, 40(11), 648–661.

Ren, A., Micura, R., & Patel, D. J. (2017). Structure-based mechanistic insights into catalysis by small self-cleaving ribozymes. Current opinion in chemical biology, 41, 71–83.

Kim, K. J., Kim, H. E., Lee, K. H., Han, W., Yi, M. J., Jeong, J., & Oh, B. H. (2004). Two-promoter vector is highly efficient for overproduction of protein complexes. Protein science : a publication of the Protein Society, 13(6), 1698–1703.

Jang, H. J., Ha, B. K., Zhou, J., Ahn, J., Yoon, S. H., & Kim, S. W. (2015). Selective retinol production by modulating the composition of retinoids from metabolically engineered E. coli. Biotechnology and bioengineering, 112(8), 1604–1612.

Guo, H., Ryan, J.C., Mallet, A., Song, X., Pabst, V., Decrulle, A., Lindner, A.B. (2020). Spatial engineering of E. coli with addressable phase-separated RNAs. bioRxiv 2020.07.02.182527; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.02.182527

Guo, H., Ryan, J. C., Song, X., Mallet, A., Zhang, M., Pabst, V., Decrulle, A. L., Ejsmont, P., Wintermute, E. H., & Lindner, A. B. (2022). Spatial engineering of E. coli with addressable phase-separated RNAs. Cell, 185(20), 3823–3837.e23.

Martin W. (2010). Evolutionary origins of metabolic compartmentalization in eukaryotes. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 365(1541), 847–855.

Hammer, S. K., & Avalos, J. L. (2017). Harnessing yeast organelles for metabolic engineering. Nature chemical biology, 13(8), 823–832.

Tsai, M. C., Manor, O., Wan, Y., Mosammaparast, N., Wang, J. K., Lan, F., Shi, Y., Segal, E., & Chang, H. Y. (2010). Long noncoding RNA as modular scaffold of histone modification complexes. Science (New York, N.Y.), 329(5992), 689–693.

Bracha, D., Walls, M. T., & Brangwynne, C. P. (2019). Probing and engineering liquid-phase organelles. Nature biotechnology, 37(12), 1435–1445.